Narrative sequencing is as

much a technical issue in writing non-fiction as it is in writing a novel. If you’re writing a history of Bullfrog County, Louisiana or a biography Brigadier Sir Henry Mandible, your

first impulse will probably be to adopt a linear, chronological approach to

your subject.

However, if you’re of a more

adventurous turn of mind, you might consider presenting your subject

discursively, as a sequence of thematically related anecdotes, reflections,

interpretive speculations and commentary. It’s a more demanding approach, but it can yield a richer reading

experience.

The discursive literary

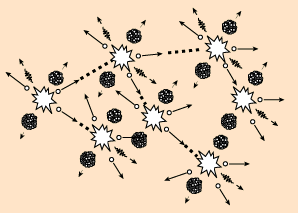

technique replicates the associative way that the human mind works. It’s a mental chain reaction. For instance, if somebody casually mentions

“September” in my hearing, the word spontaneously calls to mind a whole series

of associations. It works something like

this: September; hurricane season; sitting out Hurricane Donna with my

mother, back when I was ten; in the aftermath, seeing a 15-foot high neon

sign in the form of a bowling pin bent in half, etc. These memories in turn trigger other memories

and images from other periods of my life.

By way of demonstration: suppose you’re writing a memoir of your

life. Suppose your life experience

includes various encounters with bosses who were difficult to deal with. In a linear narrative, you’d describe each

encounter in its proper place in your personal chronology. In a discursive narrative, by contrast, you

might start up a chapter with a statement on the theme of “little tin gods”: No

matter who you are or what you do for a living, sooner or later you’re going to

have to contend with a Little Tin God. Some small-minded fathead of an office manager who likes to throw his

weight around when he thinks he can get away with it.

This paves the way for you to

present portraits of the various “little tin gods” you’ve encountered

throughout your life. Detached from

temporal chronology, you can give the chapter forward momentum by starting your

reminiscence with the least obnoxious “little tin god” and working up to the

one who was the prize arsehole of the lot. You can then cap off the chapter with an insight based on experience: A Little Tin God can only get the better of

you if you let him.

The discursive approach also

affords ways to make elegant transitions from one chapter to the next. One tactic is to pick up on some word or

phrase or image in your summation paragraph, and employ it in the opening

sentence or paragraph of the next chapter.

In the above example, you might usher in a related category of your life

experience by picking up on the motif of

not letting X get the better of you

in the first line of the follow-on chapter: If it’s not a good idea to let a person like X

get the better of you, it’s a worse idea to allow yourself to become your own

worst enemy.

Admittedly, using the

discursive technique to good effect taxes the imagination. But the end result is well worth the extra

effort.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Debby Harris is an independent editor living in Scotland. Please visit her website for more information about her editing services and fees.

Shucking the chronological approach in favor of the discursive reduces the potential for the dull lulls we all experience in our lives and opens the door to keeping the reader engaged and entertained. As you say, it's definitely worth the extra effort to create a memorable rather than a forgetable work.

ReplyDeleteGreat post, Debby!

It need not always be either/or. Raviv and Melman in Spies Against Armageddon mixed thematic treatment into a loosely chronological organization interwoven by generous cross references to anticipated and prior events. By linking major issues, they lifted their history of clandestine operations from mere recounting into a dramatic narrative.

ReplyDeleteYou big brained folks!

ReplyDeleteMy friend Kerry used a wonderful mixed version of this. Writing a sort of a travel memoir about a walking vacation in Ireland, each chapter begins with the walk she and her husband took that day, but is mostly a series of convoluted tangents about this, that, and the other thing; thoughts brought up by the circumstances of the day.

ReplyDeleteIt's a fun idea, chucking chronology.

I like that idea of picking up on a key word to lead in to the next chapter.

ReplyDeleteMorgan Mandel

http://www.morganmandel.com

This post gave me a lot to ponder, thanks, Debby!

ReplyDeleteOne must watch that structure supports meaning, though. I had a client try this with a story she had hoped would be suspenseful and it fizzled the whole thing. :-/

I can see how this would work for an interconnected series of essays, but can anyone think of expamles where an entire novel was delivered this way?

I just like the mindmapping potential - that is so ME! Christopher, this post is easier with a few cups of coffee. :D

ReplyDeleteI didn't imagine the discursive approach would totally blot out chronology. Even within related events that may not follow one another sequentially, we typically have some sort of time order. Perhaps this is a form of the integrated format Larry mentioned.

ReplyDeleteKathryn, do you think flashbacks or scenes related in retrospect would qualify as discursive structure? I once read a manuscript that had two stories -- centuries apart but appallingly similar -- told side by side, one present-day chapter or two and one or two medieval chapters in back and forth order. Rather than creating confusion, it made a unique story that kept the reader turning pages -- and stunned at how archaic some modern-day mentalities are.

Is 'forgettable' now spelled with only one t as spelled in the first blog? I do not believe it is.

ReplyDeleteGreat post! That's what I'm trying for in writing my first non-fiction book next--telling a story rather than a string of facts. Thank you!

ReplyDelete